Land promoter Leaper Land has put in a planning application for 50 serviced plots at Framlingham in Suffolk, enabling local people to build a custom or self build home of their own.

The proposals were submitted to East Suffolk Council in September 2020 following consultation with local residents, and anyone hoping to self build locally can view the application (Reference: DC/20/3326/OUT) on the councils planning website.

In particular, would be self and custom builders in the region are encouraged to leave positive statements of approval for the site, as all planning applications attract numerous objections.

The application was put together with the landowner, multi-award winning architect Pollard Thomas Edwards and planning consultancy Rural Solutions on the proposals. As a land promoter, Leaper Land works to support custom and self build schemes coming forward in rural locations, with Leaper supporting the landowner to create a viable opportunity of serviced plots.

The Framlingham site includes a range of local improvements, including work to make the Victoria Mill Road safer for a larger development, a new neighbourhood play area and improvements to drainage, footpaths and ecological enhancements. These include new native tree and hedge planting, with landscape design is by Collington Winter.

In the application Leaper Land stressed the urgent need for custom and self build housing in East Suffolk, with 410 people signed up to the East Suffolk self build register. Leaper has conducted wider research into appetite for custom and self build that indicates significant unmet demand locally.

Custom and self build are individuals who purchase a serviced plot of land and act as their own developer – whether by employing their own design and build contractor or simply configuring certain aspects of the design or finish.

Building a custom or self build home means you have the unique freedom to design and build the home that best suits your needs and requirements. You can be as involved as you want to be in the process, from working with expert designers and contractors to build exactly what you want and need, to designing and managing the entire process.

Leaper Land has proactively addressed a range of questions on its website, such as how the proposal works with the local and neighbourhood plans, such as minimum indicative housing requirements.

The proposals also include affordable housing provision, including an allocated 17 homes (34% of the total), with a mix of discounted market price, shared ownership and affordable rent.

“Our research shows there is strong demand for Custom and Self-Build homes in and around Framlingham and so our proposal, if granted permission, will make a significant contribution to satisfying that demand. We are excited at the prospect of creating a beautiful new community which closely reflects the local vernacular while also providing a unique opportunity for individuals to get closely involved in the design of their new homes,” says Ben Marten, Director of Leaper Land.

Leaper Land has also applied for planning in Child Okeford in North Dorset

Images: Pollard Thomas Edwards/Leaper Land

We’re following the story of Anne, mother of six boys who is building a home for her family and one for the grandparents on the same site. They used the Right to Build to help them escape the private rental sector, acting as pioneers for the legislation, which even the council was unsure about at the time.

A quick recap:

We had found adjoining plots both owned by public service mission landowners – church and state – and both landlocked. We probably could not afford either but could we bring other values to the table? Could we find the owner of the private road and unlock access? And could we appeal to their mission interest in helping build local communities?

My visit to the first Right to Build Expo* had got off to a good start with NaCSBA Chair Michael Holmes explaining the public service mission aspect in ‘Best Value’ (blog 4).

From there it became an investigation into community building. My husband Peter, who is an architect, had already worked out that it was feasible to build two houses on the vicarage plot (managed by the Diocese of London) and a further 4-5 units on the Enfield Council-owned plot, so a small community project was plausible.

The breakout group session led by Tom Chance, Director of the National Community Land Trust Network helped to affirm some of our ideas. Community Land Trust is a way of holding land that embodies the sort of idea for affordability that we had been thinking about, where it is secured in perpetuity (see Blog 3).

It was developed in 1969 inspired by the earlier Garden Cities movement. How you get the land is another question, but in some cases it has been gifted or sold at a below market price by some philanthropic owner, and occasionally by a council. The Community Land Trust provides a legal form to put the land into a Trust for the benefit of the community and a lot of work has been done to develop a route map for interested groups and a governance model.

We were not expecting anyone to gift us anything, and we thought either the church or the council should retain the land. But we were starting to think that if we could make something work in terms of a self build, then we should be able to make it work for others too and it could be a community. I mentioned the idea to Tom and he encouraged me to apply for their ‘first stage funding’ that would fund one of their consultants to help us develop the idea. I did this the very next day.

Michael Holmes also gave me the contact details for ‘Faith in Affordable Housing’ (aka Housing Justice) an organisation working to promote housing justice and advise the church on disposal of land for affordable housing. I wrote to them too.

But before we had much time to develop these ideas I heard from the vicar that the Diocese intended to proceed with the sale by November, so we decided to call to say we were still interested.

However, we had little idea how to negotiate, some ideas about persuading them not to sell the land but keep their ‘family silver’, an idea of working with the Council to develop both sites for a vague community housing scheme and another idea of adding value by unlocking the access road. With these ideas in mind I picked up the phone.

I had never got through to the Diocese Development Manager before, only his answer machine, but this time I did. He was friendly and I felt at ease, and to my surprise he informed me that the Diocese already owned the access road and they had bought it some time ago!

This was news indeed. Our idea of adding value looked a little naïve and now there was no mileage in it. I mentioned that I was pursuing the Right to Build both as an individual and as a community enterprise with the Council and would he be interested in combining the plots for such a venture.

He said they had been trying to purchase the plot from the Council but had not got anywhere for over two years and so the decision had been made to sell now.

At the outset the Diocese had previously obtained outline planning permission for a large vicarage. This consent was due to expire in 6 months, which meant that there was a glimmer of possibility for us.

He advised that Charity Commission rules permitted them to make an ‘off-market’ sale (eg. to us!) provided that they could show that they had achieved 10% above a market price. The market valuation was provided by auctioneers. He encouraged us to make an offer.

The plot was due to go to auction in November but we could potentially make a deal where we purchased the church land and access road for an initial sum now, but a further sum later if we managed to develop the Council site. He believed we might have more luck in the future with the Council than he had done to date.

Could we possibly do it? We knew could not buy the land on our own. The rough auctioneers’ valuation was considerably beyond our means but the plot was big enough for two houses, so would we be able to get planning permission for two houses and find someone to partner with?

And even if we could what about our idealistic economic justice ideas of land not being owned… housing for benefit of community… which we were beginning to develop? Then there was the question of the Council. I had hassled them over the summer months to find out who owned the access road. Would it change everything if they did now find out who owned it?

Read the other parts of the Self Build Family Build Blog.

Part One: Deciding to Self Build, the Turning Point

Part Two: Looking for Land in London

Part Three: The Land Value Idea

Part Four: A Small Matter of Access

Part Five: The Mystery of the Road Unravelled

Part Seven: Best Consideration Pursuing our Community Building Idea

Part Eight: Calling on Higher Parts

Photo: printed with permission of Fiona Hanson 2020©

*The Right to Build Expos were professional focussed training events sharing best practice, delivered by the Right to Build Task Force

Package home design and build firm Baufritz has been awarded a local Cambridgeshire business award in the category of Architectural Design Company of the Year 2020, for its Treehouse home.

For anyone looking for a company to design and build their self build home, industry awards are a great way of establishing the reputation of a company and its work, in the same way as viewing their gallery of case studies. Both offer an insight into the quality and reliability of the company.

Choosing the manufacturer and/or builder of your future project is one of the biggest decisions that you will make on a self build, with the biggest price tag. So getting it right is crucial, and awards can be a good piece of additional evidence.

Don’t be afraid of asking a package manufacturer if you can visit one of their built homes, or even whether they have show houses or open houses available to visit. For example, buyers of a Baufritz can, by appointment, visit its factory in Germany, to support them with the process of choosing design elements (but buyers must either have a plan or plot first). They can even choose to stay in one of Baufritz’s houses as means of trying the home, with a range of homes across the county to rent/experience.

Oliver Rehm, CEO of Baufritz in Cambridge said: “We are delighted to have won this local business award, which recognises our involvement and commitment towards the community since the arrival of Baufritz in the UK in 2006. It also proves that our approach to create prefabricated and sustainable eco houses of the highest quality are as sought after in the UK as they are in the rest of Europe.”

The Cambridgeshire Prestige Awards recognise businesses located in the East of England that provide a personal approach towards their customers to maintain a high quality level of service and experience. The judging panel based their decisions upon areas such as service excellence, quality of the product/ service provided, innovative practices, value, ethical or sustainable methods of working, as well as consistency in performance.

“Baufritz built our extraordinary eco family house in Central Cambridge five years ago. Every single day we express our disbelief and grateful thanks that we live in this gorgeous space. It truly is a modern house with soul.” Owner of Treehouse Cambridge

Check out the timelapse video of the Cambridge Treehouse being built on site

On 19 and 20 September, Bicester-based self and custom build development site, Graven Hill, will be talking all things self-build at Build It Live.

The event is going virtual this year, taking place entirely online. From the comfort of your own home, you’ll experience a whole weekend full of inspiration, interviews and top tips from a range of experts.

Graven Hill has a long-running partnership with hosts, Build It, having opened the Build It Education Hub in November 2019. Home to the site’s Marketing Suite, the Hub is a self-build project itself, giving visitors the opportunity to learn about the various aspects of building their own home, including product choice, design, and construction methods.

These are just some of the many topics Graven Hill will be exploring during the virtual event, with attendees able to book live one-to-one chats or video calls with the team throughout. Whether you want to discuss plot availability, financial options, or just have a burning question, the Graven Hill experts will point you in the right direction to making your dream home a reality.

There will be an interview with self-builders, Zakima and Sam Omotayo, as well as Graven Hill’s managing director, Karen Curtin, at 1.10pm on the Saturday. They will be speaking about why Graven Hill was right for them, their self-build process, and offering advice to prospective self-builders. This will also include a live Q&A, so attendees can ask any questions they may have to people who have experienced self-building first-hand.

Self Builders Sam and Zakima Omotayo

Zakima and Sam, said: “Being able to share our self-building journey with an audience of like-minded people is something we’re really looking forward to. Our experience at Graven Hill has been so rewarding, and if we’re able to inspire others to take the plunge then that’s the cherry on the cake.

“Self-building is an option that people rarely consider in the UK, but we’d love to see that change. We now live in a home that reflects our style and needs, and we are very happy.”

For those unsure about whether self-building is right for them, the Graven Hill team will also be able to explain the site’s custom build new homes. These take the ease of a conventional new build and combine it with the personality of a self-build. Perfect for people who want a unique home without the heavy lifting.

Eligible for Help to Buy, custom build new homes are also accessible to all, including those aiming to get a foot on the housing ladder.

Karen Curtin, managing director of Graven Hill, said: “The UK has yet to fully embrace the concept of self and custom building, and Build It Live gives us the opportunity to spread the word about its potential, as well as quash certain misconceptions. At Graven Hill, our aim is to provide an accessible route to building your dream home, something that is often dismissed due to time and cost.

“This year’s event may be virtual, but we’re certain it’ll inspire a whole new set of budding self-builders to give creating a home that fits their every need a try.”

Whether you’re looking to start a self-build project of your own or are just curious about what Graven Hill has to offer, make sure to book your place at Build It Live. For exclusive offers, speak to the site’s sales team during the show.

The last few plots are available at Ssassy Property’s Springfield Meadows development in Southmoor, offering a low-carbon opportunity to custom build your own home. The development in Oxfordshire is made up of 25 homes, with 15 sold, seven reserved and the last few homes available for purchase.

The homes are being built using Greencore Construction’s Biond System, an offsite timber frame method that uses a hemp-lime, which is capable of delivering high performance, zero carbon homes. The homes are all set on generous plots with private gardens and shared outdoor spaces, including a pond and orchard. 15 of the homes on the site are custom build, with nine affordable homes.

Ssassy’s commitment to green technology underpins its projects, and makes Greencore Construction an excellent partner for its green build method. The UK Green Building Council states that roughly 40% of the UK’s entire carbon footprint comes from the built environment, with half of this stemming from energy used in buildings and infrastructure, such as roads and railways.

This makes it imperative that new homes should embrace greener methods, that contribute less both during the construction and usage of the building. Check out its guide to climate change in relation to new building and review the carbon impact of the decisions you make on your own project.

Springfield Meadow’s green credentials earned it One Planet Living Global Leader status by Bioregional, who stated:

“The use of an innovative construction system using natural materials like hemp will create an approximately 90% reduction in carbon emissions due to construction compared to a standard home in the UK of a similar size.”

Ian Pritchett, Managing Director of Greencore, explains the build system. “The timber frame building system is insulated with Lime-Hemp and natural fibre insulation. These natural materials absorb carbon dioxide during growth.

“We also build using the Passivhaus principles to reduce energy use, while integrated solar panels in the roof supply as much energy as the homes requires over the course of a year. To complement this, we incorporate nature as much as possible through working with the Wildlife Trust, provide an electric car club and generally support the new community to live as sustainably as possible.”

Land promoter Leaper Land has submitted an outline planning application for a 65-plot site on the edge of the village of Child Okeford. Routes to home ownership at Child Okeford include self-build, custom-build and custom-choice, with the custom-choice built to a shell stage, at which point it is handed over to the purchaser.

Routes to ownership at Child Okeford:

Self-build individuals buy a serviced plot, with details of what is allowed to be built set out in a design code and with a palette of materials to choose from. As the design code is pre-approved for planning, permission is guaranteed as long as your build meets the conditions set out in it. Buyers can also choose to project-manage themselves or commission a developer or housebuilder to build the home.

Custom-build with this model, you buy the plot, with the design code setting the context, and contract directly with a developer to build the house. On this scheme, this route offers less of flexibility as there is a choice of designs with pre-prepared layouts and specification options that are approved by planning.

Custom-choice this option involves a developer building your home to the wind-and-watertight structure shell, at which point you take over to commission the remaining jobs. Buyers will pick from a range of interior layouts and specifications.

Street view of Child Okeford scheme

While the self and custom build routes offer stamp duty savings and exemption from the Community Infrastructure Levy, custom choice enables people to access regular mortgages and Help to Buy. This extends the site to a greater number of buyers.

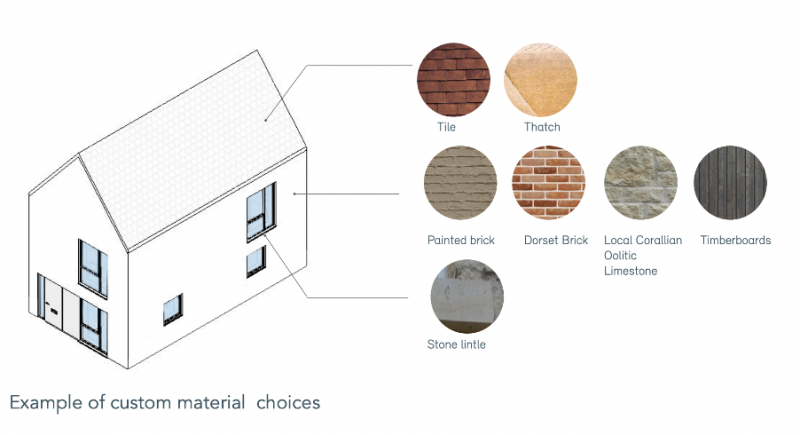

The homes are controlled by a design code, which is quite strict as it sets the context for the development, in response to the rural nature of the site. This gives the buyers choice, such as a range of materials, shown below, but by controlling this through a design code it ensure the designs are in keeping with the village.

Child Okeford custom build homes – material palette showing choice for exterior materials

“Design codes are really important as they offer reassurance to both the planners and the local community that something of quality will be built. So residents can choose from a palette of materials, for example, all of which could be seen on buildings in the village, helping the scheme at Child Okeford fit in,” said Ben Marten, Director of Leaper Land.

Bringing forwards land for development is costly and time consuming, which is where a land promoter comes in. They act on behalf of the landowner, using their skills and knowledge to secure a planning application.

As such, land promoters can help unlock small parcels of land that otherwise might not come forward. This may be because these sites are too small for big developers to be concerned about, but too costly or time consuming for an unexperienced landowner to bring forward by themselves.

Therefore, they are an ideal solution if you are a farmer or other small landowner who sees potential in their site, but are not sure how to proceed. Typically, their costs are based on results, which makes them a good choice for such landowners.

If you are planning to build, sign up to your local Right to Build register – you can find out the details on the Right to Build Portal.

Once planning is granted they will be in touch with more information and expected times for plots to come to market.

Images: Pollard Thomas Edwards/Leaper Land

We’re following the story of Anne, mother of six boys who is building a home for her family and one for the grandparents on the same site. They used the Right to Build to help them escape the private rental sector, acting as pioneers for the legislation, which even the council was unsure about at the time.

A quick recap:

We had found two plots of land, adjacent to one another, one owned by the Council and the other by the Diocese of London. We’d made contact with both of these public service mission landowners, but had we come any nearer to getting a plot for our family home?

Having tracked down the Disposals and Acquisitions Manager (see Part 3) at Enfield Council, I gave him a call. I am not sure what I was expecting, but to my surprise he was an accessible man, warm, friendly and straight talking.

I explained the Right to Build and our desire to remain in the local area, which he deemed reasonable enough. I mentioned that we had identified a couple of council plots and shared my fears that we could not compete with well-resourced Property Developers but he was encouraging. In fact, he reckoned would-be owner-occupiers should be able to outbid developers who have to make profits over-and-above the costs.

However, this was simply a nice way to say that the council was obliged to get full market price on the open market!

I explained that our challenge was that we just wanted to build a family home, whereas a developer might build a lot of flats and outbid us that way! Or just sit on the land waiting for it to increase in value.

I pointed out that this was a growing trend in our area; numerous ‘luxury’ small apartments sold as investments or ‘easy commute from Eurostar and Heathrow’. These commuters would not be building communities or committing to the area long term.

The Disposals Manager got the point and said he would look at the site. He vaguely remembered talking with the church but the site was small, he was understaffed and it was landlocked. He promised to get back to me.

A plot with no access – or is there?

This was interesting; there was a little cul-de-sac and both the church plot and council plot seemed to have access off it. However, the one catch was that it was a ‘private road’.

I had not heard of such a thing or imagined it. It is a fact of life that a house needs a drive or an access to get to the front door. It may be just a strip of pavers but if one stops to reflect for a moment it is a big deal!

That connection to one unremarkable road is a connection to all roads, all houses, all shops – and in this case no development could take place without the access. How had it come about? Was all the land free and then some bits got turned into private houses and gardens? Or was it all private and some bits carved out and given to Her Majesty on our behalf?

The church plot was the unused end of a 170ft long garden. Similar garden plots of the neighbours were developed in 1990 into 3 red brick family houses and the cul-de-sac. After they sold the houses many developers would have got this road ‘adopted’.

This means that it is taken into the public road network, with the developers or owners no longer responsible for the maintenance. But that had not been done in this case, meaning that both plots were landlocked.

Who owned the road? Would they refuse access? Could they demand a Queen’s Ransom?

Perhaps this was our opportunity? It was too small a site for the Council to be much bothered with. But for us it was worth our while trying to unlock it, both for the Church and for the council, and perhaps creating an opportunity to use part of the site for a house for ourselves. Naive? Almost certainly, but hope springs eternal!

My husband had an idea that if the owners of the close wanted an excessive fee, then there might be an alternative solution for access through the vicarage plot – not that the church would want that but it could be a bargaining point. It was a glimmer of an idea.

I spent the next few weeks and months chasing the Disposals Manager and his assistant and looking for the owner of the close. I tried the Land Registry and Highways department but no luck. It turns out that it is far more difficult to get information from the land registry for a piece of land, like a road, that has no specific house address.

Subsequently I found that you can do a detailed map search to identify land but at the time the closest I came was to find out who the developers were of the houses on the close and get their accountant’s details from Companies House. I left a message and emailed asking if I could get into contact with the Developers. The council had not fared any better finding out who owned the road.

It was at this time that I saw an advert for the first ever ‘Right to Build Expo: Unlocking the Potential of Custom & Self Build Housing’. I immediately purchased a ticket and rather amused myself by signing as ‘Director, Fennell and Sons’ – true in a practical sense although it would make for interesting discussion if asked what my company did!

On the day I sat at the front and asked the first question. ‘The Right to Build has given hope to families like ourselves but public bodies such as the Council or Diocese have a duty to get Best Price for their land. How can we compete with a better resourced developer for these plots?’

It was the Chair of the Conference and of National Custom and Self Build Association, Michael Holmes, who gave me the answer: ‘It was not ‘Best Price’ that public bodies such as the Council or Diocese had to get but ‘Best Value’.

This was a significant difference. Best Value was not limited to solely monetary considerations – it should take into account wider benefits to the community and longer term cost benefits beyond the initial receipt for disposal of land. The real obligation would be to deliver value in terms of the public service mission that is their reason for being.

Could we and other families prove ‘best value’ in our desire to build up communities and commit long term? – This was our next challenge.

Read the other parts of the Self Build Family Build Blog.

Part One: Deciding to Self Build, the Turning Point

Part Two: Looking for Land in London

Part Three: The Land Value Idea

Part Four: A Small Matter of Access

Part Five: The Mystery of the Road Unravelled

Part Seven: Best Consideration Pursuing our Community Building Idea

Part Eight: Calling on Higher Parts

Photo: printed with permission of Fiona Hanson 2020©

The Cambridge cohousing scheme, Marmalade Lane, has won the top award at the Royal Town Planning Insitute’s Awards 2020, adding to its already sizeable list of awards. Marmalade Lane was awarded the RTPI’s Silver Jubilee Cup having been entered by Greater Cambridge Shared Planning Service and development company TOWN, which is a NaCSBA member.

A first for Cambridge, the Marmalade Lane cohousing scheme was given the top prize as the judges felt that it demonstrated the value of community-led housing and a collaborative approach to planning.

The judges commented that the development puts the needs of the residents at its heart, and has created a distinctive and sustainable neighbourhood that was full of character.

Sadie Morgan, design industry leader and Chair of the judging panel, said: “Marmalade Lane shows the importance in new housing developments of greater local participation, increased opportunities for accessing nature and the prioritisation of people over cars – its design has helped create a place with a genuine sense of belonging and a rich local culture that harnesses the humour and warmth that are so vital in these challenging times.”

Cambridge’s first cohousing project has its roots in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, when the developers left the land in limbo. A cohousing group had formed in Cambridge, then called K1 Cohousing, and was looking for land, and the council supported the process of allocating the site for cohousing.

Working with community housing consultants Stephen Hill and Adam Broadway, they paved the way for the group to create Marmalade Lane and build the homes that supported them in the way they wanted to live.

Rather than pursue self build, Town was brought on as the developer, working with Mole Architects and Scandinavian eco-house builder Trivselhus to design and build the scheme on behalf of the residents.

The project is made up of 42 homes, customised to the residents preferences, but using a limited system of choice to ensure designs were replicable and cost-effective. This resulted in three house types, with 27 layout options, with mortgage finance provided by Ecology Building Society.

The result is a scheme of terraced houses and apartments, set around shared gardens and a pedestrianised play street, with a common house for socialising and cooking shared meals, should people wish to eat as a group.

Cohousing is a form of community-led housing, where people come together to build and live in an ‘intentional’ community, with shared values. This may work with other community solutions, such as a Community Land Trust – which holds the land the project is built on in perpetuity, although this is not the case at Marmalade Lane.

A core principle is that most cohousing projects have shared elements. These often include a common room for socialising, but may include shared guest suites to keep spare rooms to a minimum, laundries, kitchens, and shared external design features, such as orchards, play streets, car parks, gardens and so on.

All the houses and flats have their own facilities, such as kitchens, so it is very much based around people wanting to live as part of a community, but they can still live independently. Costs and maintenance of the communal facilities are shared, so there’s typically a rosta for jobs.

But it represents a different way of living from the typical UK experience, where people and community underpin the homes, making it a transformative route to housing, that is growing in appeal.

We’re following the story of Anne, mother of six boys who is building a home for her family and one for the grandparents on the same site. They used the Right to Build to help them escape the private rental sector, acting as pioneers for the legislation, which even the council was unsure about at the time.

Our situation had become pressing – we were due to be turned out by our landlord of 10 years, we couldn’t afford to buy, and, as a family of 8, no one wanted to rent to us. So we decided to look at building our own home. In Part 2 we heard about the Right to Build, started looking for land and made contact with the Council.

So we were under way – our adventure had begun! We were stepping into the dark and I found myself enjoying the process. There was excitement in the chase, especially using a piece of legislation that neither we nor those we talked to really knew how it worked. We were making it up as we went along, and success or failure was not an issue (at least at this point), leaving us free to experiment.

Believing in the Right to Build somehow gave our aspiration life, and windows started opening. At this point we weren’t even sure if we could afford to do it, after all, can you build where you can’t afford to buy?

Peter (my architect husband) said there was a development rule of thumb: 1/3 for the land, 1/3 for the builder to build the house and 1/3 for the developer. We didn’t really know what was in the Developer’s 1/3, but knew that part of it must be wages, profit and fees, and we reckoned we could save on some of these.

But by how much remained elusive, for example, could the 33% be reduced to 13% and secure for us a house at 80% of market price? Probably not, and even 80% was beyond our budget!

We knew that most of what is referred to as ‘house prices’ is not about the house but about the land. So it can be argued that house price inflation in cities is actually the rise of land values over time.

Peter said that houses are like cars: they drop in value with age as they get closer to needing an MOT or the roof repaired. This is a simple and obvious truth once seen, but families miss this point, even while they feel the wrong of working hard and not being able to afford a house. Peter came across these ideas through an evening class called ‘Economics With Justice’.

The course puts forward the argument that society would be more equitable if inflated land values were retained for community uses. He wondered, could there also be a fix for the affordability problem in this? What if we didn’t actually have to buy the land?

Hearing about the Council’s duties under Right to Build had got us thinking about Council-owned land. Surely the Council must also be interested in answers to the affordability problem?

Here was the revolutionary idea– having found a Council plot, could we persuade the Council NOT to sell it to us?

As previously explained, It had been difficult getting to meet the Enfield Development Manager in the first place, and getting a post-meeting response was not much easier.

I eventually secured one by copying in our local MP, and when it came it was a full and considered response. It included the contact for the Right to Build in the Housing Team, an acknowledgement of the Council’s duty under the Right to Build Act and the information that 210 ‘interested parties’ had signed up to Enfield’s Right to Build register (at April 2017).

It was difficult trying to establish the right person to talk to about a plot, as it turns out that Housing, Property and Planning are all separate departments, something I had not realised. And naturally, they don’t necessarily talk to each other!

I thus went from a contact in Planning to a Housing contact to a Property contact (none of whom had a brief on the Right to Build) until I was finally given the email of someone with the title of Property Disposal Manager. I had finally got to a contact for someone who would be able to talk to me about the plot. It had taken a while and in the meantime another possibility emerged.

Every so often I go to the local church toddler group, and sitting round the table with my youngest on my lap the conversation turned to our housing situation. I’d plucked up the courage to discuss our hope of building, even though I was a bit nervous about discussing looking for land in London, as it seemed so unrealistic. But to my surprise the vicar’s wife said: “They are selling the land at the bottom of our garden – the Diocese have been talking about it for years”.

I went home and looked up the plot, and whether it was coincidence or fate, the garden plot backed directly onto the Council plot I had already been looking at.

So there was another Development Manager to talk to – this one for the Diocese of London. I emailed and asked about the plot and got an immediate reply. His reply was gracious.

They were indeed looking to sell the plot at some point although they were also trying to acquire the Council plot and they were obliged by Charity Commission rules to get best value. We now had two plots of interest and two public service mission landowners who might be willing to not sell to us.

We had made contact with the two property departments, although we didn’t want to tell them we were actually hoping not to buy; they wanted to talk to buyers!

We wanted to engage with them, and at the same time find out who might have the political mission to think about the wider issues around society and the affordability question.

Read the other parts of the Self Build Family Build Blog.

Part One: Deciding to Self Build, the Turning Point

Part Two: Looking for Land in London

Part Three: The Land Value Idea

Part Four: A Small Matter of Access

Part Five: The Mystery of the Road Unravelled

Part Seven: Best Consideration Pursuing our Community Building Idea

Part Eight: Calling on Higher Parts

Photo: printed with permission of Fiona Hanson 2020©

Celebrity architectural designer Charlie Luxton has been working with the community of Hook Norton, Oxfordshire, as they work to create a community-led affordable homes scheme, which has recently applied for planning permission. Once approved, the scheme will create 12 dwellings set around a new communal landscape, with a community building providing a new village hub.

The Hook Norton Low Carbon Trust kickstarted the project by identifying a neglected piece of council-owned land, and worked with Cherwell District Council and other stakeholders to develop the idea of a sustainable and affordable housing project. The scheme has been planned to provide homes for local people in housing need in the community, with a strong local connection, using a Community Land Trust model that assures the affordability remains in perpetuity.

Community engagement was a crucial element throughout the scheme, helping to shape the homes, designed by Charlie Luxton Design, to meet local ambitions to boost sustainability. The project has set the target of being carbon neutral both during construction and occupation, and will incorporate renewable energy sources, with its own micro grid.

In addition, the project will include a flexible multi-use space, laundry and cafe, with overflow bedrooms for residents, as well as resources for wider village use, including a workshop and communal ‘library-of-things’.

“Hook Norton Community Housing is a project by the people of Hook Norton for the People of Hook Norton,” said Charlie Luxton. “It has grown out of local need for sustainable affordable housing for the residents of our community, that 150 new developer led homes in the village have failed to deliver.

“Working with Cherwell District Council, the land owners and others local organisations the project has been design with extensive continuity consultation, over 15 events and intersections to provide 12 Passivhaus Plus flats and a community building with laundry, workshops, cafe and a library of things.

“Not only are the flats and facilities prioritised for people with local connections, it is planned for construction to be undertaken by small/medium local contractors to ensure as much of the build spend stays in the community. This project is trying to show that housing can be about people and the planet before profit.”